Substrate-associated Plants: plants that Forsyth tells us are associated with acidic/sandstone places like the Hocking Hills.

Mountain laurel, Kalmia latifolia (left) is native to eastern US and has been grown as an ornamental since the 1700s. Despite being a shrub, this species can grow up to 40ft tall though it has a slow growth rate. As the flowers bloom the filaments bend under tension, creating a trigger effect that shoots pollen when bumblebees make contact [source].

Eastern hemlock, Tsuga canadensis (right) is a native evergreen tree that can grow up to 160ft tall. The bark was commonly used to tan hides, as well as a poultice for bleeding wounds. The inner bark and leafy twigs can be made into a tea for a variety of ailments [source].

Chestnut oak, Quercus montana (left) is a member of the white oak group, of which most species display a yellowing of leaves (chlorosis) in high pH soil. The bark of this species is also used in tanning because of high levels of tannic acid [source].

Blue ridge blueberry, Vaccinium pallidum (right) is a native shrub in the blueberry family that grows up to 3ft tall. Can you guess why wildlife love it? Yeah, it’s the blueberries. The plant can spread through underground runner roots and is fairly drought tolerant, but is not tolerant to alkaline soils. [source].

Biotic Threats to Forest Health: trees severely affected by specific insect and/or fungus diseases here in Ohio.

Butternut, Juglans cinerea have had their population significantly reduced due to a fungal disease, the butternut canker or Ophiognomonia clavigignenti-juglandacearum (what a mouthful!), that causes cankers to form on the branches and trunk. It wasn’t discovered until the 1960s, but coring analysis indicates infection as early as the turn of the century. The US Fish & Wildlife Service classifies butternut as a species of concern, largely due the effects of this fungus. Conservation efforts focus on breeding live specimens because Juglans seeds of all kinds cannot be stored long-term. There has also been talk of breeding resistant strains, but it is very difficult to test resistance level [source].

Apparently I didn’t get a picture of the American chestnut, so here’s eastern hemlock Tsuga canadensis again! There are actually several insects and diseases that hemlock trees are commonly afflicted by, and its often a combination that takes individual trees out [source]. Insect pests include elongate hemlock scale, hemlock looper, spruce spider mite, and hemlock borer. The two diseases are needle rust and Sirococcus tip blight. Arguably the most severe attacker in Ohio is the hemlock woolly adelgid, which suck sap from the tree and reproduce rapidly. They can kill an entire tree within one season [source].

Appalachian Gametophyte:

1. Among fern species with long-lived gametophytes, perhaps none is as peculiar as Vittaria appalachiana. Set forth its common name and describe the manner in which it is so remarkable.

Appalachian gametophyte, Vittaria appalachiana is one of just three species (all ferns) in which the plant is made entirely from asexually reproducing gametophytes; mature sporophytes have never been observed.

2. Fern gemmae are differently sized than spores. Describe the consequence of that size difference in relation to dispersal. State three possible agents of gemmae dispersal. A 1995 publication by Kimmerer and Young is cited as evidence for one of the modes. What is that evidence?

Fern gemmae are much larger than spores, which means they only disperse a short distance through wind, water, or perhaps animals (compared to long distance wind dispersal for spores).

3. The notion of limited dispersal capability in V. applachiana is also supported by consideration of a combination of the geologic history of area, and the current distribution of the plant. Explain this evidence and how it supports a particular time frame for its loss of the ability to produce mature, functioning sporophytes.

This species is absent north of the extent of the last glacial maximum, despite a transplant study showing their capability to survive beyond that point. This indicates that the current distribution is due to spore dispersal at one point from a functioning sporophyte. The species limited range in southern NY indicates that gametophytes lost their ability to produce functioning sporophytes “sometime before (or during) the last ice age” (Kimmerer & Young 1995).

4. Could the current populations of the Appalachian gametophyte be being sustained by long-distance dispersal from some tropical sporophyte source? Support your answer. What is the most likely explanation for the wide range of V. applachiana?

Past allozyme (variant forms of enzymes which differ structurally but not functionally from other variations, determined by alleles at the same locus [source]) studies have provided a basis to reject that current populations are being sustained long-distance from a tropical source. Additionally, monophyly analysis suggests that dispersal from tropics happened only once.

Your specific assignment: two examples of mosses.

Delicate fern moss, Thuidium delicatulum is a 2-3 times pinnate carpet moss (pleurocarpous). It is found on acidic soil or humus in damp woods, prairies, etc. across North America [source].

Pincushion moss, Leucobryum glaucum is aptly named with its perfectly round appearance. Some insect species are adapted to feed on this members of the pincushion moss, but this moss group also contains toxic substances to deter consumption [source].

Miscellaneous Other Observations:

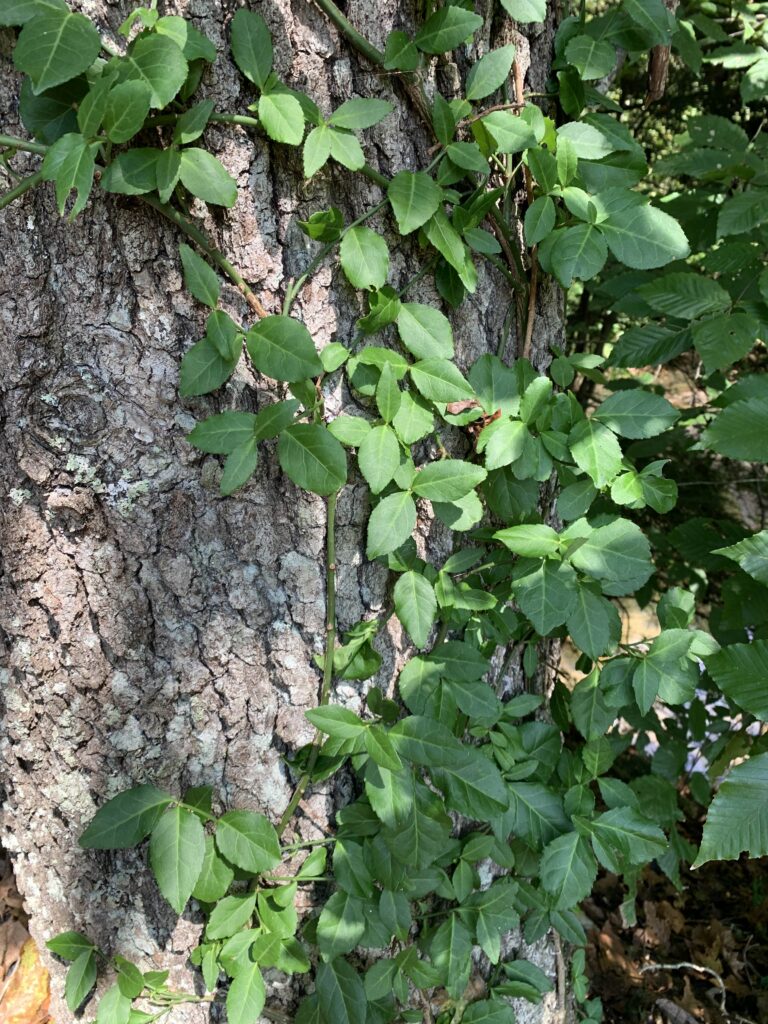

Fortune’s spindle/wintercreeper, Euonymus fortunei is actually a shrub despite the climbing tendencies exhibited in younger specimens. Native to Japan, this invasive species can dominate small and medium-sized trees [source].

Beechdrops, Epifagus virginiana (left) is a native flowering plant that is parasitic to beech trees. Because all energy is acquired from the host, there’s no need for leaves or photosynthesis. The flowers self-pollinate while closed, and the flowers that do open are often sterile [source].

Pinesap, Hypopitys monotropa (right) is a native but rare indirect parasitic wildflower across the US and Canada. It obtains energy from conifer tree roots by a middle man: mycorrhizal fungal hyphae [source].

Liverwort subspecies, genus Calypogeia (left) is easy to identify but very difficult to categorize into species. Many of the species distinctions are at a cellular or individual leaf level, which this picture won’t be much help for. Very pretty!

Broom forkmoss, Dicranum scoparium (right) is a native moss that is very common, found in almost every state and almost every Ohio county [source]. The species is easily recognized by its perfectly coifed hair — I mean by its long and narrow leaves swept to one side (secund).